In his latest book, ‘The Last Oil’, SalmonBusiness editor Aslak Berge gives the barnacles-and-all account of the rise and fall of whaling – and explains how the money made in this extraordinary boom is still shaping the modern world.

Every year, as the austral summer reaches its peak in the Antarctic, the oceans burst into life. Nourished by the 24-hour daylight, enormous clouds of phytoplankton blossom in the icy currents. Billions of krill gather to feed on these blooms. With them, come whales.

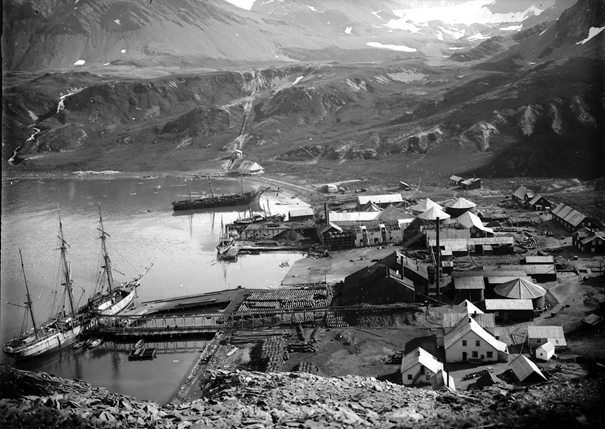

Berge’s story begins in 1904 with the establishment of the first Antarctic whaling station station at Grytviken on the tiny island of South Georgia. Backed by Norwegian, British and Argentine capital, South Georgia quickly became the epicentre of the world’s whaling industry. Within a few years the Antarctic was producing about 70 per cent of the world’s whale oil.

Behind this boom was the extraordinary demand by multinationals for the raw material for margarine and soap. By the end of the era, the Antarctic Blue Whale, the largest animal to have ever lived, was all but extinct.

The book was launched on Amazon this week.

Over six decades of hunting – until the factory ship ‘Kosmos IV’ anchored for the last time in Sandefjord, Norway in the late 1960s – it is estimated some 1.3 million whales were killed around Antarctica alone.

But Berge reveals more than a simple environmental cautionary tale. In his book, he follows the money from the blubber cauldrons of South Georgia to the shimmering towers of the city of London – to examine how this gold rush shaped the development of financial markets, consumer goods and capitalism.

Here, he talks to SalmonBusiness to reveal how his interest in the subject came about, the links between salmon farming and whaling, and his next project:

How did the project come about?

I got the idea as a student, learning about the booming whaling industry in my financial history class. We were, however, presented only fragments of a history that made me really curious. A few years later I visited Leith, Edinburgh, at a salmon conference, and read about the Salvesen family’s business venture in Antarctica. The Scottish family were the biggest whalers of this period, and I didn’t have any knowledge about this. I thought this industry was totally dominated by Norwegians. That made me even more curious.

Do you have a personal connection with the whaling industry?

No, the only personal connection I have is the fact that my aunt’s father was a whaler.

Readers might be surprised to learn about the connections between farmed salmon and the whaling industry. Can you explain how you came to learn about this?

First of all, both were start-ups. Young industries that were developed by pioneers on the back of a strong global demand for marine resources. Secondly, they are both capital intensive, risky, dividend yielding stock market favorites. Both industries were developed on licenses, investing in processing capacity both on land and at sea. Just as the old giant floating whaling processors we now see a development with offshore salmon farming – and even more capital intensity. Industrial whaling turned into a biological tragedy. I hope that will not be the case for salmon farming.

Were there things in this story that surprised you?

The biggest surprise, I think, was to explore how deep multinationals such as Unilever went to get hold of fat resources for their mills – to produce soap and margarine. Quite history literally moving into “The heart of Darkness”.

What is your next project?

I’ve got several book projects I’m working on. The next one is called “Goldfinger – the history of Mowi”.