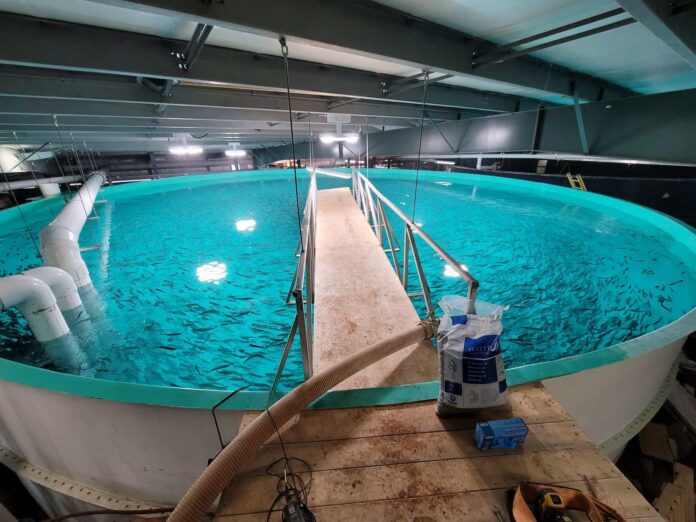

As the debate over the future of aquaculture intensifies, Ivar Warrer-Hansen traces the evolution of recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS) and hybrid flow-through (HFT) systems, offering insights into their potential—and pitfalls—in the future of salmon farming.

There has been much debate recently about the future of salmon farming, particularly following Canada’s decision to ban cage farming in British Columbia. Discussions have centered on Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS) and Hybrid Flow-Through (HFT) systems.

However, confusion persists—what exactly is HFT, and why do opinions on RAS differ so widely? After all, a RAS is a RAS, so why do some claim they work while others say they don’t?

RaboResearch: The technology set to transform salmon farming

HFT is far from new. In the modern aquaculture era, attempts to operate “modern” HFT systems were carried out with carp production in the 1950s and 60s in East Asia, mainly in Japan. However, they were not called HFT systems; they were called re-use systems, as opposed to full flow-through systems.

The reason for the introduction of re-use systems there was mainly to compensate for water shortages during drought periods. These systems were not very intensive and were producing fish (carp) that were very tolerant of poor environmental conditions. Even going further back, it has always been more or less a standard in the trout farming industry for the last hundred years. They have re-used water one way or the other.

New kid on the block

RAS came onto the scene later. It started indirectly, as sporadic research was conducted at a number of universities in Europe and the US into systems where water was purified and re-used to allow fish to be kept in research facilities for prolonged periods of time. The technologies were often associated with those used for aquariums and were not designed with commercial aquaculture in mind.

It was not until the late 1970s that ideas of intensive commercial RAS emerged. Some of the first pioneering work was conducted at the Water Quality Institute (now DHI Group) in Denmark. In 1980, the Danish Shell Oil Company commissioned the institute to build a fifteen-tons-per-annum eel RAS—in principle, the world’s first commercial intensive RAS.

This model was the start of the “boom” in the early 1980s of eel production in RAS in Denmark, Germany, and Holland, which soon reached an annual production of 8,000 tons—a significant contribution to European aquaculture at that time. This development spread further afield, even as far as China, where many eel RAS plants were built in the mid to late 1980s.

Teething problems

These first systems, however, faced many teething problems. The first mistake in RAS development was adopting the same mechanical and biological treatment methods as those used in municipal wastewater treatment plants. This was a field with years of experience, and it seemed natural to copy those methods. However, in an aquaculture situation, the priority is to remove or reduce substances that are or can be toxic to fish, mainly ammonia and nitrite. This means that nitrification is the most important function in a biofilter in a RAS. In municipal sewage treatment, the targets are often organic matter and nitrate. In other words, the wrong technology was chosen at the start, and the first RAS were far from optimal. However, eels were relatively tolerant, and despite the poor designs, eel farmers “got away” with it. In fact, they made good money due to the high price of eels.

So why do some people say RAS works and others say it does not? Well, the fact is, some RAS work and some do not. With some RAS suppliers (even some who have been in the business for a long time), there is still a lack of understanding of some important details in RAS. The main issues are biofilter design and functioning, sludge removal strategies, pipe design, and fish logistics.

There are some RAS suppliers who still hold onto fixed-bed biofilter technology, where sludge accumulation takes place. This can pose risks of both methane and hydrogen sulfide formation. While these filters have good abilities to remove fine particulate matter, their performance will not match that of MBBRs. That said, there are some RAS suppliers who have made improvements in their fixed-bed filter designs and reduced these risks, but the risks remain. Equally, there are also poorly designed MBBRs, but on balance, MBBRs have the edge. Still, in choosing a concept, it is not an easy world to navigate.

The fact remains that there are some RAS concepts that work very well and will be good candidates for future salmon production. The fact also remains that some HFT systems will work very well. However, in the latter case, it will be highly site-specific how well they work. One will probably see more RAS in the future.

Ivar Warrer-Hansen is the CEO of RASLogic, winner of the 2024 Scandinavian Business Award for Best Food Tech Consultancy.