Salmon farms, camels, and chaos: Britain’s reluctance to innovate laid bare.

There’s an old joke that a camel is just a horse designed by committee. In Britain, though, we don’t stop at camels. We’d spend three years commissioning a feasibility study, debating whether the camel’s humps might be offensive to local artists, and end up with a press release proudly announcing the world’s first hump-neutral donkey.

As the UK government pivots toward an ambitious agenda for growth—with Labour leader Keir Starmer vowing to “take the brakes off Britain” by cutting through the red tape that hampers critical infrastructure projects—it’s worth examining how this drive aligns with debates in other sectors, including aquaculture.

The ongoing saga surrounding the proposed semi-closed salmon farm in Loch Long provides a striking example of the anti-innovation, anti-growth mindset that continues to stifle progress in industries vital to the UK’s economy and food security.

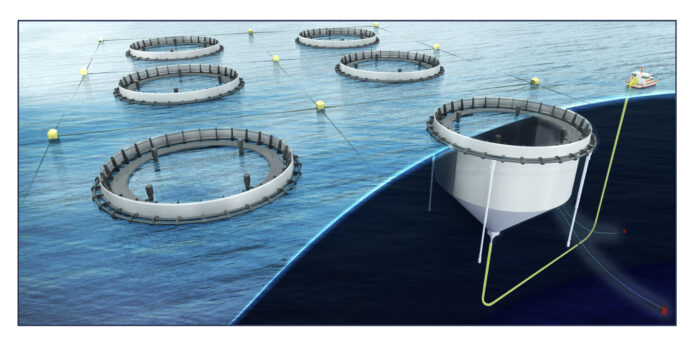

The proposed semi-closed salmon farming facility at Loch Long has been a point of contention since its inception. Brought forward as an innovative solution to some of the environmental challenges associated with open-net salmon farming, the project aims to use impermeable enclosures to reduce negative interactions between farmed fish and the surrounding marine ecosystem.

Called-in

In 2022, the Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park authority rejected the proposal, citing concerns over its potential impact on the waters and surrounding wildlife of Loch Long. Following the rejection, the decision was appealed and later “called in” by Scottish ministers for further review. Three years later, and the fate of the project remains undecided.

Now Green MSP Ariane Burgess has had her say: In a recent statement, Burgess criticized the proposal, stating, “Loch Long is renowned for its natural beauty, wildlife, and cultural heritage. The proposed salmon farm could scar the loch’s iconic coastline and harm its wildlife.” The area is home to seals, otters, seabirds, and endangered wild salmon in the connected Endrick Water, a protected habitat.

Burgess, who backs a moratorium on new salmon farms, added: “Salmon farming is an unsustainable and often very cruel practice. We urgently need to consider how much of our seas we are giving away to an industry which is doing so much harm to marine life and our environment.”

While the technology—involving impermeable floating enclosures—promises to mitigate environmental impacts by isolating farmed fish from the surrounding marine ecosystem, critics have labeled the project as “scarred coastline” waiting to happen and questioned its scalability. Yet, this very skepticism toward innovation reveals a broader resistance to change that could have serious consequences for both the aquaculture sector and the UK’s economic ambitions.

Reckless experiment?

Let’s be clear: the Loch Long project is no reckless experiment. Semi-closed systems are already being trialed and adopted in other parts of the world, and their potential to reduce interactions between farmed and wild fish has been widely acknowledged. If Scotland wants to maintain its position as a global leader in sustainable aquaculture, it cannot afford to dismiss such advancements outright. Instead, it must adopt a measured approach that balances environmental stewardship with the need for innovation and growth.

This tension between progress and opposition is emblematic of a broader issue plaguing the UK: a pervasive “challenge culture” where well-organized pressure groups wield legal tools and public sentiment to obstruct projects that serve the national interest. As Starmer’s government has noted, this culture has delayed major infrastructure initiatives for years, adding unnecessary costs and frustrating attempts to modernize industries and boost GDP. The aquaculture sector, already under pressure from global competition and sustainability demands, is no exception.

The stakes are high. Aquaculture contributes significantly to Scotland’s economy and the global food supply, and the need for sustainable solutions has never been more urgent. Rejecting projects like Loch Long not only undermines the sector’s ability to meet these challenges but also signals a troubling resistance to the kind of bold thinking that drives economic growth.

The debate over Loch Long isn’t just about a salmon farm; it’s a test case for whether the UK can reconcile its environmental priorities with its economic aspirations. If Britain is serious about building a more dynamic, forward-looking economy, it must confront the “no at all costs” mindset that threatens to derail progress across sectors. Aquaculture, with its potential to combine innovation, sustainability, and economic growth, should be part of that vision—not a casualty of shortsighted opposition.

The question is: will Britain embrace progress, or will we keep arguing until the horse has emigrated to New Zealand?