Dead deer legs are being placed in the River Muick, Aberdeenshire, Scotland, to help boost salmon survival rates.

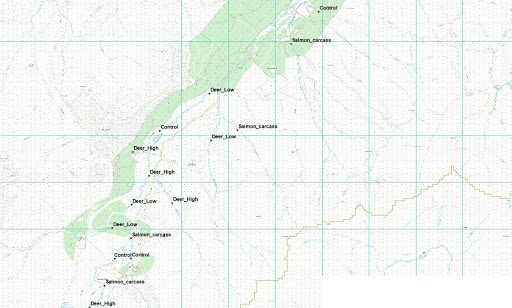

The River Dee’s fisheries board and trust have partnered with the James Hutton Institute to test the impact of the initiative. The 3-year trial is taking place at 16 points at the River Muick, with legs from locally culled deer being placed at various points along the river.

Streams that lack dead adult salmon have fewer insects so that the surviving fish fry are smaller and belong to fewer families. The resulting loss of genetic diversity could make these salmon populations more vulnerable to extinction in a changing world.

In recent years due to low numbers of returning adult salmon very few carcasses now contribute to the nutrient status of upland streams.

“It’s to see if we can use deer legs as a substitute for salmon carcasses. There are less fish returning to our rivers because there are less fish dying after spawning. 50 years ago, thousands of fish would be coming into our Scottish rivers and around 65% of them would die after spawning each year. But those numbers have gone way down in recent decades,” explained River Operations Manager Edwin Third in an email to SalmonBusiness.

The idea of nutrient addition is commonplace in parts of the United States, and the trial will assess if the use of deer lower legs leads to similar increases of macroinvertebrate and fish biomass as salmon feed pellets, which are also being placed at sites.

The trial is using deer legs sourced from local estates. When butchers harvest deer, everything gets used, including the skin and the meat but the head and lower legs are normally wasted and are deposed of in a dry pit. Those nutrients are then lost.

“A lot of salmon restoration is expensive, but here we can recycle stock and the nutrients can be put back in the system replicating salmon carcasses. The legs are broken down and cause an increase in growth of plants and insects, which in turn are eaten by juvenile salmon,” explained Third.

“The deer legs are cabled together with steel wire in groups of 5 or 6 and pinned to the river bed with 1m long steel pins and weighed down in place with a rock so we can monitor them,” he added.

Though the thought about using deer heads would be too “grisly”, Third explained that he felt a duty to look alternative methods. “Salmon have been around for 60 million years – we need to do everything we can to protect and restore our valuable wild salmon stocks.”