“Fur used to turn heads, now it turns stomachs”: Could salmon be next?

In November 2020, reports of dead mink rising from their graves in Denmark made international news.

The macabre story was the result a rushed cull of the country’s entire mink herd over fears of a coronavirus mutation that led to 17 million animals being slaughtered and buried in shallow pits.

More than 1,000 mink farms in Denmark were ordered closed as the world’s largest producer of the animals terminated all operations, virtually overnight.

The cull led to a political crisis in Denmark, with opposition parties accusing the government of using the pandemic to try to terminate the country’s increasingly toxic fur farming industry.

They may have been onto something.

Nearly every top designer – including Vivienne Westwood and Burberry – had ditched fur, 14 EU states have banned its production, California has banned the sale of it, Queen Elizabeth II renounced it, and top retailers such as Selfridges and Topshop refused to sell it.

By the time the pandemic hit, the industry was already facing significant challenges. Overproduction, reduced demand, and a strong online anti-fur movement had caused a substantial decline. That same year, the world’s largest fur auction house, Kopenhagen Fur, closed its doors for the last time.

The market’s value which – despite decades of protests – was still worth as much as $40 billion in 2015, had worse than halved by 2020.

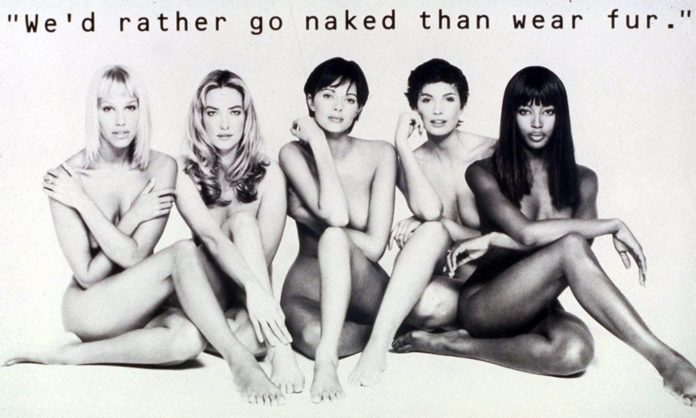

Thirty years after five models, including Naomi Campbell, told the world “I’d rather go naked than wear fur” for a PETA campaign, the European fur industry is in the final stages of collapse.

Peta volunteer flour bombed Kim Kardashian for wearing fur in public. pic.twitter.com/MU1siD30gI

— Keveyem (@Keveyem) January 15, 2017

Turning heads

Using a mix of shock tactics and skilful public relations work, activists have won the culture war over fur. The steady drip of negative publicity has turned the industry into a byword for callousness and suffering.

Its a play book that anti-salmon farming activists have leaned on heavily, cheered on by a coalition of opponents within the international media.

For anyone working in the industry, these protesters can easily become a kind of background noise, easily blocked out or dismissed as fanatics. In recent weeks, however, a string scandals, accompanied by distressing photos and videos have challenged that complacency.

As a senior executive in the industry told SalmonBusiness, “One day we will wake up and find that consumer opinion has shifted and the industry won’t know what hit it.”

That moment may be happening he warned, pointing to the massive publicity generated by Icelandic singer Bjork’s recent interventions.

“It’s not about paying more attention to the protestors,” he said. “It’s about asking producers whether they really have so much confidence in their brand that they think they can safely ignore public opinion?”

The aquaculture industry remains one of the greatest engines for wealth creation of recent times. Salmon farming has created thousands of jobs, transforming the prospects of communities around the world, providing billions of consumers with a healthy, affordable protein at a fraction of the environmental cost of some of its competitors. But after a month of negative headlines and with everyone from Björk to David Attenborough lining up to put the boot in, is a moment of reckoning coming for the industry?

If you throw enough red paint, eventually it will start to stick.

Matthew Wilcox is editor of SalmonBusiness.

Activist banned from going within 50ft of Mowi’s salmon farms in Scotland