Ottawa sends negotiator to Eastern Canada after several communiques and reports identify First Nations interest as key to salmon-farming expansion

Ottawa has appointed a federal fisheries specialist to negotiate in Eastern Canada with indigenous people now seen as the key to government plans on extending salmon-farming rights.

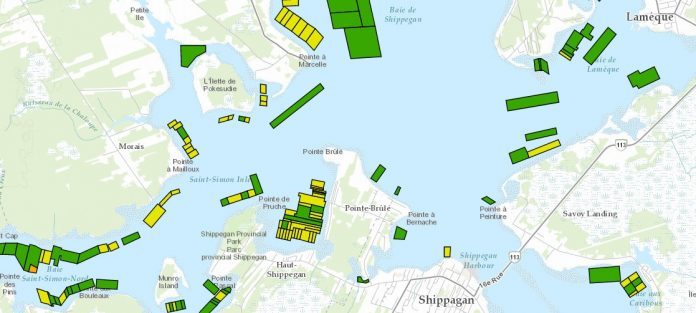

A recent industry report, government statistics and recent statements from Ottawa confirm federal authorities aim to expand aquaculture licensing still confined to one percent of suitable areas. To open those areas, Canadian laws will compell Ottawa to negotiate with indigenous communities on behalf of corporate aquaculture interests with competing and complementary fisheries rights that include aquaculture.

“No relationship is more important to our government than the one with Indigenous Peoples from coast to coast to coast,” Fisheries Minister Dominic LeBlanc was quoted as saying. “We are committed to reconciliation and to an improved future for Indigenous Peoples.”

On the West Coast, meanwhile, the leaders of Canada’s original population have increasingly agitated either for the expulsion of corporate salmon-farming or for the preservation of their own aquaculture enterprises. In some cases, government has felt compelled to support protestors representing mixed interests and exploiting limited First Nations ire at the presence of aquaculture.

Without agreement in Canada’s East, indigenous holdings could put a similar protest-based stopper to salmon-farming expansion in the Maritime provinces.

Federal Fisheries negotiator, Jim Jones, will now be thrown into the fray, ordered “to advance negotiations towards the reconciliation of fisheries rights in the Maritimes and Quebec with Mi’kmaq and Maliseet First Nations and the Peskotomuhkati”. In this “broader reconciliation effort” led by Jones lies the hope for “greater self-determination” on one side and “22,000 jobs” and another “250,000 tonnes” of farmed seafood on the other (two-thirds of it likely to be salmon).

Mr. Jones

Fist Nations leaders now see the potential for wealth-generation in the coastal communities where Jones is heading. The government may be hoping to secure something more valuable than the 20 “agreements” with indigenous peoples that allow for 75 percent of current salmon production in British Columbia.

A new deal for the Maritimes, Canada’s eastern provinces, could set the region apart with a better salmon-farming agreement for all. It might also see more of the model Marine Harvest Canada has developed for operations across Canada.

“MHC operates in the traditional territories of 24 unique First Nations, and has formal agreements with 15 Nations and 7 First Nation-owned businesses. One-fifth of our workforce is Indigenous peoples,” said company spokesperson, Ian Roberts, in a letter to SalmonBusiness. He confirmed that consultation with First Nations is the Federal Government’s responsibility, although MHC have tried to be “good neighbors” and has “continued to engage” with First Nations leaders.

New deal, or fear

A new deal for Maritime Canada First Nations, however, could be more commercially inclusive, judging by industry’s new appraisal of their leaders.

“Supported by business-savvy leadership and a development-friendly agenda, more and more (indigenous communities) are looking for opportunities to become business owners, and for someone to help them along that path,” the Canadian Aquaculture Industry Alliance reported to last week’s policy conference in Ottawa.

See Canada could triple grow-out

See Grieg hope renews on Canada megaproject

A 2015 report on commercial fish-farming benefits for aboriginals by consultancy RIAS suggested First Nations could also try growing smolt using on-land RAS facilities. In 2014, however, Namgis First Nation were already growing Atlantic salmon on-land near Port McNeil on Vancouver Island, although financial struggles have beset the facility and other land-based projects worldwide.

In the East of Canada, First Nations have seen firsthand the pitfalls of salmon lice. “In the absence of effective sea lice treatments available in Canada, salmon farming companies have had to fallow numerous sites in New Brunswick,” the 2015 report said. Yet, according to another study, New Brunswick was also an area where, over 10 years, salmon-farming revenues could grow fivefold to CAD130 million, a potential seen in other provinces, especially Newfoundland, where First Nations participation has the numbers to grow.

The warnings, however, are never far off: While some First Nations aquaculture initiatives have met with “notable success”, those of others “have met with notable failure”, the report said.

Harmony needed

“In some cases, this lack of success has intensified pre-existing economic challenges within the community,” the Minister was advised. “These failures have undoubtedly discouraged other First Nation communities from seriously considering the economic development potential of aquaculture.”

“The failures have also contributed to the view among some economic development agencies and venture capitalists that First Nations aquaculture is a ‘high risk’ venture — a view that is currently limiting the ability of First Nations to access the capital necessary to fund their aquaculture ventures.”

The RIAS report, however, referenced an earlier report saying First Nations need not focus on fish husbandry to be successful. Indeed, more participation in “the supply and service sector” might be part of Jones’s mission. It might also be about letting established business create jobs.

Before that happens, capital-wielding players will need certainty.

“In this new era, MHC will not apply for new farms in First Nation territories without support,” Roberts said.

“When First Nation governments oppose salmon farms which currently operate with permits and licenses received from Canadian authorities, and many sites have done so for over 30 years, we will work all governments to find negotiated solutions.”

So, while a new deal for the Maritime First Nations of the East might comprise dozens of B.C.-style agreements, it might also include more ownership stakes in licenses or promises of long-term commercial cooperation. On the Canadian West Coast, 28 First Nations have salmon-farming in their traditional territory “and participation in salmon aquaculture continues to increase.”

Both reports for Ottawa cited in this story suggest First Nations are sure to get guidance in the coming negotiations from business-support groups in their communities. SalmonBusiness aims to follow the process in future reporting.

If Ottawa’s Mr. Jones gets it right, participation in salmon-farming that includes ownership rights, supply agreements and marine services could define a new deal for the East.