Marine Harvest bought their fish farming success formula from two pioneering brothers.

There’s nothing new about cultivation and artificial hatching of trout and salmon eggs. Already in the mid-19th-century initiatives were being taken in this field. Farming of freshwater trout dates right back to the 1750s in Germany. But the leap from fresh water to the sea occurred in Norway, or to be more precise, in the district of Sunnmore.

Tentative attempts had been made long before in brackish water, including in Loddefjord on the outskirts of Bergen, but it was two brothers from Sykkylven who were to succeed in systematizing this work.

Salmon in captivity

The two brothers Karstein O. (born 1919) and Olav C. Vik (born 1912) dug out a dam on the family farm, which was situated on the banks of the river Vikelva. This was for the purpose of keeping brood salmon that had been caught in the Sykkylvsfjord. They knew that salmon could be kept and fed in captivity. In 1955 the Vik brothers dug out three earth dams; one for sea water, one for fresh water and one for brackish water.

“In May-June we caught a few salmon in a wedge net and released these in seawater dams, and after assimilation over to fresh water where the salmon were milked in the autumn and the eggs delivered to the hatchery,” Olav Vik told author Erna Osland in her book “Bruke havet – pionértid i norsk fiskeoppdrett” (1990) (Exploiting the sea – the pioneering era of Norwegian fish farming).

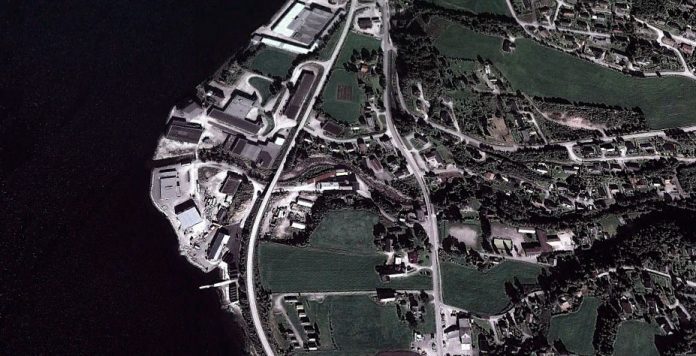

The hatchery was located at Straumgjerde in the furthest reaches of the Sykkylvsfjord.

Growth quicker in sea water

They experimented with farming rainbow trout in the fresh water dam, and this attempt served to show that rainbow trout grew considerably quicker and bigger in sea water.

From 1959 they experimented with releasing trout and salmon into floating wooden crates. First 5×5 meters, then 10×10 meters. This was the starting point for the subsequent development of farm cages.

“We counted the first six years as experimental years, we recorded and systematized, found out how much salt was tolerated by the eggs and fish,” said Olav Vik.

Problems with quality

In 1959 Karstein Oddmund and Olav Vik established the company Nor-Laks, which produced both smolt and market-ready, edible fish. However, the flesh of the fish was white in color, which prompted the brothers to start experimenting with shrimp shells in the feed. Norwegian customers were somewhat unresponsive to the product, and thus most of the fish were sold to Sweden.

However, sales weren’t enough to pay the bills, so they worked elsewhere; Karstein as an architect, and Olav as a gardener.

The Norwegian authorities were ambivalent about the activity, but the goings-on at Vikoyra had caught the attention of the world outside Norway. Via ‘salmon’ Professor Jones at the University of Liverpool, Karstein was invited to Cambridge’s “Salmon Research Group” to speak about the experiments.

Here he met with representatives from the multinational food corporation Unilever.

The Unilever deal

In 1964 the brothers signed an agreement with Unilever on a facility that was to be built according to their design. For this, they received a total of GBP 20,000.

“The agreement with Unilever was really a bilateral agreement; they gained knowledge from us and vice versa. But Unilever went on to employ ten biologists and set up high fences around their plant. After that, we were ‘shut out’ so to speak. But, we had the money and that enabled us to survive. We built an acclimatization facility for the smolt/juveniles, pump stations and cold storage plant,” Karstein recounted to author Erna Osland.

The Unilever Research Laboratory set up a research station on the school site in the western Scottish village of Lochailort.

The operation was duly named Marine Harvest.

In 1963 Nor-Laks began using wellboats for transport of salmon and rainbow trout smolts that had adapted to sea water. After 25 years in fish farming with high levels of biological and financial risk, the Vik brothers sold out of Nor-Laks – to Unilever.