The debate over land-based salmon production continues to heat up, with proponents of Hybrid Flow-Through Systems (HFTS) and Recirculation Aquaculture Systems (RAS) often pointing fingers at one another. While HFTS is technically sound and relatively simple—lacking the biofilters that can complicate operations—its economic viability remains unproven. When assessing past failures, however, RAS projects have encountered significantly more financial and technical setbacks.

The first land-based salmon RAS projects, launched between 2010 and 2012, included Langsand, Danish Salmon, Jurassic Salmon, and Swiss Alpine (now Swiss Lachs). Later, Atlantic Sapphire entered the scene. Yet none of these projects have achieved more than 50–60% of their design capacity. The primary reasons for these failures include:

-

Overly ambitious production and biological plans

-

Flawed RAS design and poor system execution

-

Biological challenges and misperceptions

Overly Ambitious Production and Biological Plans

The early RAS projects relied on assumptions about fish growth rates and stocking densities to build their business models. Growth rates are largely temperature-dependent, while stocking density determines the required tank volumes. A well-structured production plan should also account for daily feeding rates and water flow requirements, which influence the capacity of the water treatment system.

Because RAS projects faced higher capital expenditures (CAPEX) than traditional sea cage farming, they needed to demonstrate a competitive edge. Optimistic spreadsheet projections suggested that controlled environments would drive better growth rates, making RAS a viable alternative. However, these assumptions were often overly ambitious, resulting in underperformance and financial losses.

Flawed RAS Design and Poor System Execution

Many in the industry argue that land-based salmon farming is still in its infancy, and that there is an inevitable learning curve. Nonetheless, some RAS suppliers failed to adapt and refine their designs. Key issues included:

-

Repeated hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) incidents

-

Inadequate biofilters leading to inefficient waste treatment

-

Systems unable to handle projected feeding rates

The biofilter is the heart of a RAS facility. If it is ineffective, no other component can compensate. Moving Bed Bioreactors (MBBRs) have proven superior to fixed-bed biofilters. In Norway, more than 100 hydrogen sulfide incidents have been reported in smolt and post-smolt systems since 2016—almost all in fixed-bed systems.

Langsand Salmon, one of the early RAS projects, suffered massive fish losses due to hydrogen sulfide buildup in its fixed-bed filters. These filters tend to accumulate organic particles that decompose into sludge, increasing the risk of hydrogen sulfide formation if not managed correctly. Even sub-lethal exposure can stunt fish growth. Fixed-bed filters also create favorable conditions for the microflora responsible for off-flavors in fish.

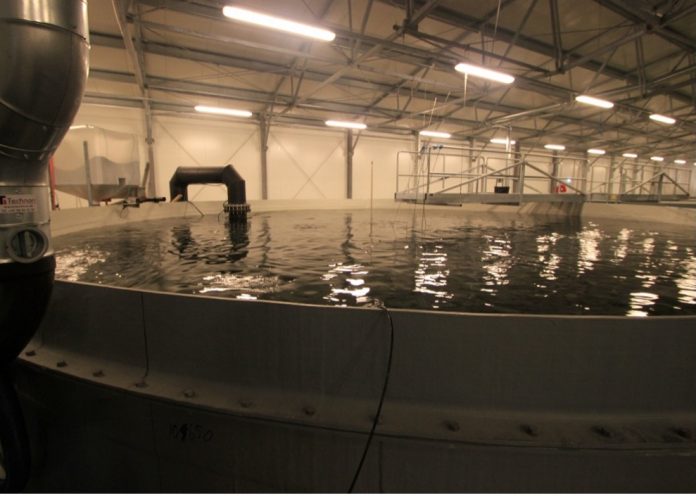

Interestingly, while these land-based RAS projects were still being developed, some Norwegian post-smolt RAS facilities were already successfully producing fish up to 500–1,000 grams. These systems used large tanks similar to those in early RAS farms but were based on MBBRs, which proved highly effective. They could easily have produced grow-out fish at a financially viable scale. Skagen Salmon, the only land-based salmon RAS project to achieve consistent success, is based on this technology. Had more RAS suppliers adopted MBBRs earlier, many costly setbacks and legal disputes could have been avoided.

Biological Challenges and Misperceptions

Understanding the biological requirements of salmon is crucial for successful aquaculture. Early RAS projects relied on knowledge from traditional sea-based farming, where conditions differ significantly from those in a controlled RAS environment.

One major mistake was setting water temperatures too high in the hope of achieving faster growth rates. While salmon do grow more quickly at 16°C than at 12°C, prolonged exposure to high temperatures triggers early maturation, stunting growth. Production plans failed to account for this, forcing companies to sell fish at suboptimal weights—often below 2 kg—and fall short of production targets.

Stocking densities were another area of misperception. Early plans assumed densities of 100–120 kg/m³ were acceptable, but experience has shown that 80 kg/m³ or lower is more appropriate for optimal fish health and growth.

The Future of Land-Based Salmon Farming

With better understanding and improved technology, RAS-based farming is proving viable—as demonstrated by Skagen Salmon in Denmark and, more recently, Danish Salmon’s new extension. As more projects refine their systems and learn from earlier mistakes, the question remains: will RAS or HFTS ultimately prevail?

While HFTS may offer some advantages, the controlled environment, biosecurity benefits, and the ability to locate farms closer to market suggest that RAS will likely have the edge in the long run.

In the years ahead, we will see which approach emerges as the industry leader. One thing is clear: only those willing to adapt, learn from past mistakes—and this is where many fall short—and implement sound biological and engineering principles will succeed in land-based salmon farming.