The legendary commodities trader Marc Rich more or less single-handedly developed the spot market for oil.

“The difference between an obstacle and an opportunity is often of minor importance. The wise man uses both to his advantage,” said Niccolo Machiavelli. This is precisely what many salmon traders have pondered a lot, in a market where minimum prices, punitive duties and import bans have been part of everyday life for the past 40 years.

A trader’s basic business idea is to buy, sell, store and transport products. The core has historically been buying and selling – trading. The principles are the same whether you trade grain, salmon or oil.

No one has done it sharper on raw materials than the media-shy and now deceased Marc Rich.

Read also: These grain traders control the raw materials for the feed

Survival

In the book “The King of Oil – The secret lives of Marc Rich”, written by the Swiss Daniel Ammann, Rich lifts the veil and tells how he built up his commodity empire:

“It’s only a good deal when the two signatories are laughing together at the table. That’s the only way a partnership can have any future. Otherwise it’s the only deal you’ll make.”

Jewish Marcell Reich escaped with his family in his father’s newly purchased Citroën when Germany attacked Belgium in the spring of 1940. They hurried with everything they owned, drove through France and got out of the country on a cargo ship in Marseilles. The family escaped to the United States, where they settled. With this background, the survival instinct was absolutely fundamental in his future work.

The merchant’s son Marcel Reich, who changed his name to the more Americanized Marc Rich, got a job with commodity trader Philipp Brothers in 1954. He had an elephant’s brain, and soon advanced from the mail department to the trading desk. Here he started shopping for raw materials. First mercury, tin and aluminium, later also oil.

But the latter market was earmarked for the few.

The so-called Seven Sisters, consisting of Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (now BP), Shell, Standard Oil Company of California (now Chevron), Gulf Oil (Chevron), Texaco (Chevron), Standard Oil Company of New Jersey (now Exxon) and the Standard Oil Company of New York (Exxon), controlled 95 percent of the world’s oil trade. Almost everything went through their value chains. But a wave of nationalisation, not least in the Middle East, the rise of OPEC, and the market power the organization exercised, was to change this.

Information

As a key figure in oil trading at Philipp Brothers, Rich would establish himself as a friend of the unpopular. He cultivated close relations with the Shah of Persia, who secretly supplied a pipeline in Israel and through it sold oil to Franco’s Spain.

The legendary commodities trader more or less single-handedly built up the spot market for oil.

A key driver was access to unique information – before the market. Sitting close to the decision-makers in OPEC, not least the major customer Iran, made Rich and his team well informed.

“I wouldn’t call it inside information, but direct information,” says one of Rich’s Iran traders. “Unlike other companies, we were present, we were there. Unlike them, we got all the information available in the market.”

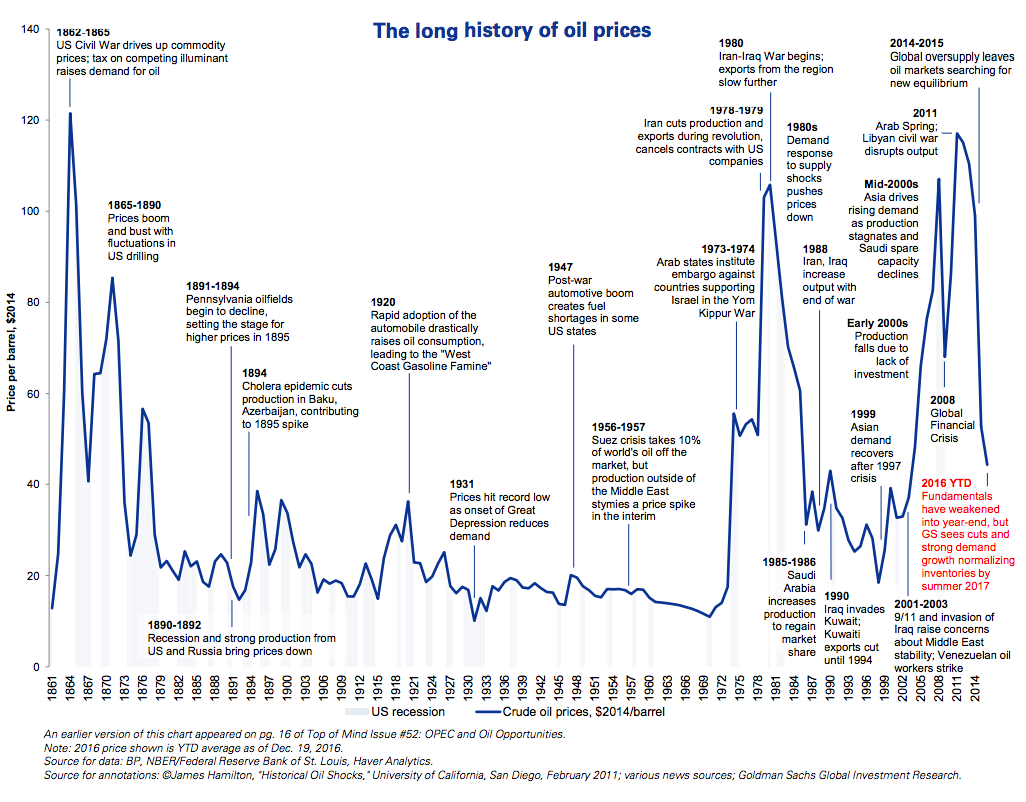

In the spring of 1973, he bought a total of one million tonnes of oil, equivalent to 7.5 million barrels, at five dollars a barrel. The deal was made without a permanent buyer, so not so-called back-to-back. The management at Philipp Brothers was shocked by the big contact. The company’s motto was “It’s better to sleep well than eat well”, which meant they liked low risk. Rich was forced to sell, at a loss.

He had had enough. Rich took a handful of his closest associates, as well as their best clients, and started out on his own.

Because the analysis had been a bull’s eye.

Israel was attacked by several of its Arab neighbors in October, the so-called Yom Kippur War. Western arms supplies helped Israel hit back hard. OPEC responded by turning back the taps. The price of oil tripled.

Risiko

Rich located the business in the small Swiss town of Zug. By locating the company here, he enjoyed several advantages: Switzerland is politically neutral, and at the time was not even a member of the United Nations. Zug is close to the financial center of Zurich, where the big banks have particularly strong secrecy. Zug is also a tax haven with very low income and corporate taxation.

Marc Rich + Co. was an immediate success. Already in the first year of operation, in 1974, the company had a turnover of more than one billion dollars and had a net profit of 28 million dollars. In 1975, the result rose to 50 million dollars, and the following year the company earned 200 million dollars.

A key reason was precisely Rich’s willingness to take chances. He operated with much greater risk than his old employer. He had analyzed the oil market and was sure that prices would rise.

“The most important thing for a trader is to see opportunities. The others didn’t see what I saw,” says Rich. He saw trends and developed markets.

The Soviet Union supplied Cuba with cheap oil. It was Rich who did the transactions and delivered the oil. But instead of transporting oil entirely from the Soviet Union, he instead obtained supplies from Venezuela. This allowed him to sell the Soviet oil at full price on the world market.

Efficiently

Rich chartered large tankers, which had previously barely existed outside the network of the Seven Sisters. Without this, the spot market could not be developed. Thanks to the spot market, customers no longer had to depend on a single company to control the entire value chain from the oil wells to the petrol pumps. Many countries, with limited experience in oil trading, could now themselves offer their oil for sale. The spot market was much more efficient than the seven sisters’ oligopoly.

Towards the end of the 60s, only five percent of the world’s oil was traded outside the seven sisters. Ten years later, half of the oil was traded in the spot market – at market price.

Increased oil prices led to increased exploration activity and investments. It opened up new fields in more expensive areas such as the North Sea, Africa, south-east Asia and Latin America. Rich bet on long contracts with new oil countries such as Nigeria, Angola and Ecuador, from the mid-70s. In five years, the start-up company was transformed into a trading empire.

The great coup came in connection with the revolution in Iran, in 1979, and the subsequent war against neighboring Iraq. Rich maintained his relations with Iran’s national oil company, even after the Shah was overthrown and the country was led by the clerical government of Ayatollah Kohmeini. The so-called OPEC II crisis tripled the price of oil again.

In 1980, Rich + Co. has sales of $15 billion, more than the national budget of many of the countries they traded with. In the same year, the major supplier Iran had taken 53 American citizens hostage in the American embassy in Tehran. They were kept there for 14 months. It was going to be a game changer.

Hunting

Countries such as Angola and Zaire were underdeveloped, also in terms of morals and law. Rich had no qualms about supplying countries such as South Africa, Iran and Cuba. He traded with both Israel and Iran. Arab countries and the Apartheid regime. Marxists and Capitalists. He could do most things for money.

South Africa paid a premium of eight dollars per barrel in a contract for 36 million barrels of oil. Rich made $230 million from this deal.

“The concept of trading is to provide a service. Trading is business in service. We bring buyers and sellers together and earn a service fee,” says Rich himself. It is the same principle that Ayn Rand advocates: “In every agreement, you act according to the trader principle: You give value and receive a value.”

Relations with Cuba and Iran were to suffer. In 1983, Rich was sued for the largest tax evasion of all time in the United States. State Attorney Rudy Giuliani smelled blood and demanded a long prison sentence. Included in the charge, as perhaps the most important point, was that Rich had traded with America’s enemies. Rich, who was now a Swiss citizen living in Switzerland with a Swiss company, denied breaking any laws. Switzerland rejected US requests to extradite the financier. Rich was hunted by the FBI for three decades, before he was controversially pardoned by President Bill Clinton in 2001.

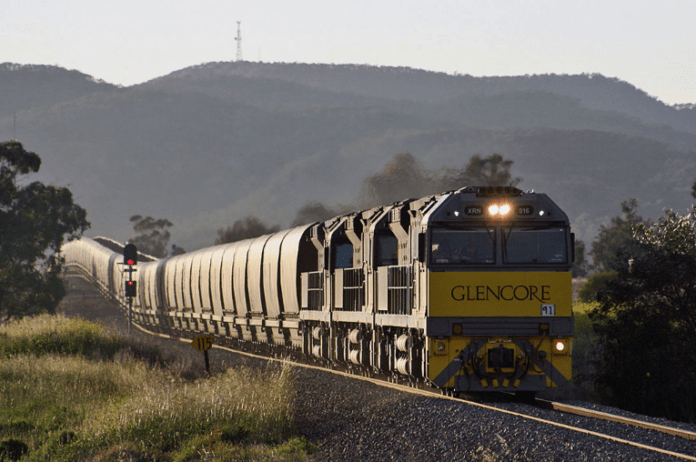

By then, Rich had long since sold out of the company he had built up himself. The employees took over and renamed it Glencore. Glencore, which was later listed on the stock exchange in London, is to this day the world’s largest commodity trader, with a 2021 turnover of 203.8 billion dollars.

Marc Rich died in 2013.