Emergence of larger and more efficient wellboats follows the same development as the large tankers.

Shipyard owner Christen Christensen wanted to bet. Together with grocer Thor Dahl, he converted the steamship “Admiral” into the world’s first floating whaling processor in 1903. It was a floating factory. After two seasons off the islands of Spitsbergen, they sent the “Admiral” and two whale boats to the Falkland Islands and South Shetland. The flotilla was met with exceptionally cold weather and a lot of ice late in the autumn of 1905. The boats were not ice-prepped. But the crew saw a lot of whales, and they were easy to catch.

“It was calm, almost curious,” the shipping company Ørnen’s annual report stated.

They returned to the Falkland Islands in weather that was “very unfavorable with storm surges” with a catch of 183 whales and 4,200 barrels of whale oil. The result was a lean profit. They prepared a new expedition in the same autumn. “The Admiral” took 336 whales, a doubling, the second season.

Freight ships

It was green field development. That was also the case when Johan Lærum & Co in the spring of 1968 picked up smolt in Tveitevågen on Askøy, outside of Bergen, Norway. The following year, the fish farming initiative of Johan Lærum & Co was put into a new joint venture, 50/50 owned together with industry conglomerate Norsk Hydro. The company was baptised Mowi.

“The fish were sent by boat to Flogøy. There were freighters carrying live pollock and herring. The wellboat was 12m long, and one could hardly see it from the dock,” Hans Øyvind Svensvik, head of Mowi’s brood fish department in Tveitevågen, previously told SalmonBusiness.

The industry was about to be industrialised. Whaling also followed that pattern.

“Dear Chr. Fredrik. I intend to build a new floating processor 20,000-25,000-tonne steam or diesel-powered with the greatest possible boiling capacity and cooking arrangements, which you’ll find most advantageous. Yours sincerely, Anders. PS: I’m also going to have 7-8 whaleboats. Connect with Smith’s Dock. It’s urgent…”

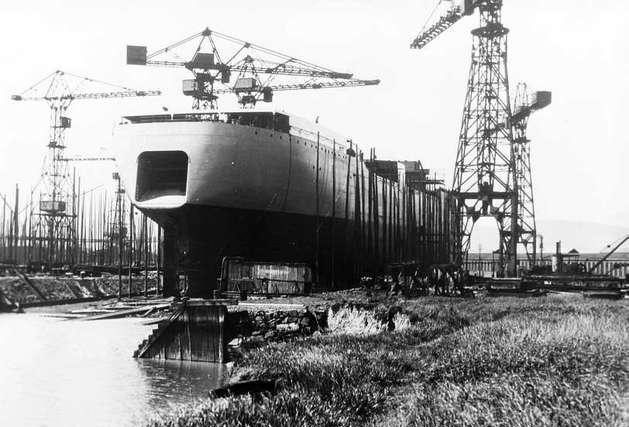

Shipping pioneer Anders Jahre wrote the letter to engineer Chr. Fred. Christensen in Newcastle. The order went to the Belfast shipyard Workman, Clark and Company in January 1928. Now it was time to bet properly. In October of that year, the limited liability company Kosmos was established with financial support from De-No-Fa, Fred. Olsen, AP Møller in Copenhagen and Lazard Brothers in London. The IPO of NOK 1.85 million (EUR 0.2 million .ed) was the largest ever in the sector.

Soon the huge ship’s body was up in the shipyard in the Northern Irish capital. The factory ship “Kosmos” was a marvel. The ship had its own reconnaissance aircraft on board, and was the first to use sonar. With a load capacity of 22,500 tonnes, she was not only the largest floating processor the world had ever seen. She was also the world’s largest oil tanker. The construction price for “Kosmos” was GBP 275,000, excluding cooking equipment.

“Kosmos” did not disappoint. Along with seven whaleboats, the colossus produced 119,400 barrels of whale oil in its first season. Over 1,000 blue whales were shot, processed and cooked. Production costs per barrel at “Kosmos” were almost half of the average Norwegian Antarctic expedition. After two seasons, the company was debt-free. And shareholders had received a 40 per-cent dividend.

The world’s largest

Industrialisation has moved forward, with many historical parallels to salmon farming. In the winter of 1995, the shipping company Laksetransport built the world’s largest wellboat. “Caroline” could load 70 tonnes of live fish – twice as much as competing wellboats. The ship’s owner Paul Martin Grønnvedt had raised EUR 1.4 million. The construction work was carried out in cooperation between two tender yards, Sletta and Vågland.

“Kosmos” had been a combined whaling and oil tanker, like many others. This was a particularly lucrative business for whalers such as Jahre, Rasmussen, Christensen and Dekke Næss during World War II. The Allies insatiable oil needs and shipping across the world’s oceans prompted the need for large tankers. The “Kosmos” was among those that were sailing for the Allies – until the autumn of 1940, when the ship was sunk, with 106,000 tonnes of oil on board, by the German auxiliary cruiser “Thor”. But the reconstruction after World War II required both more and larger tankers. The closure of the Suez Canal, in 1956, meant that oil had to be transported over significantly longer distances. The capacity of the tanker fleet was stretched thin. This required much larger tankers. In 1958, the American shipowner Daniel K. Ludwig built the first tanker over 100,000 tonnes.

Profit

The trend of larger vessels also applied in the wellboat segment. This was special freight. Larger load volume resulted in lower shipping costs per-fish. It provided cost savings for customers, salmon farmers, and profit for the shipping companies. At the same time, global salmon production increased, and the fish were farmed in larger cages. This required different tools than before. In 2007, the wellboat company Rostein was able to take delivery of the 66m “Ro Master”. Equipped with two tanks, with a load capacity of 2,800m3, it was undisputed the world’s largest wellboat.

Back to the tanker market. During the wars in the Middle East, in 1967 and 1973, the Suez Canal closed again – over long periods of time. This favoured large tankers, so-called Very Large Crude Carriers (VLCC). Jahre and another whaler, the Greek Aristotle Onassis, were among those who built VLCCs. So did other big ship owners, such as Stavros Niarchos, Sigvald Bergesen and Hilmar Reksten. In the winter of 1972/73, Reksten had welcomed three newly built VLCCs, at 290,000 tonnes each. He had now bought an industrial area at Hanøytangen, not far from Tveitevågen on Askøy, where he planned to build oil tankers up to 800,000 tonnes.

On 9 January 2019, “Ronja Storm” was launched. Sølvtrans’ new flagship was 116m long and had cost EUR 50 million to build. Shipping owner Roger Halsebakk had long ago negotiated and signed a long-term agreement with Australian Huon Aquaculture for the new build. The world’s largest wellboat was to carry fish in Tasmania, on the other side of the globe.

Late to the party

In the wake of the October war, during Yom Kippur in 1973, OPEC countries turned off the oil taps. Oil prices tripled. The freight volume shrunk in. Combined with an oversupply of ships, the effect was dramatic. Newly built supertankers were laid up. The shipping crisis would affect both the 70s and 80s. The shipping party was over.

In July 2019, shipowner Helge Gåsø announced, in a text message to SalmonBusiness, that his Frøy Rederi had contracted the world’s largest wellboat. The wellboat, which was not yet named, will be 83.2 m3 long and have a width of 30.9m. Frøy’s new wellboat can fit 7,500m3 of water in the tanks. It is larger than, “Ronja Storm”, which can hold 7,450m3 of water. Gåsø’s new build was still not delivered when the shipping company Seistar announced just before Christmas 2020 that it has contracted two new wellboats, of 2,200 and 8,000m3 in cargo volume, respectively. That means a deadweight of 12,000 tonnes, which then becomes the world’s largest of its kind. Both vessels will be built at Cemre Marin Endüstri in Turkey, and will be delivered from the yard in 2022/2023.

In 1979, the “Knock Nevis” was built at Sumitomo’s shipyard in Yokosuka, Japan. It was an ULCC, Ultra Large Crude Carrier. The ship had a load capacity of 564,763 tonnes. But it came too late for the party. The giant tanker would later change its name to “Jahre Viking”, and was scrapped in 2009.

Sources:

“Den siste olje,” Octavian Forlag 2019

Wikipedia